Ancient Mindfulness

/A hunter using handmade tools must be completely alert to the smallest signs of prey. A gatherer constantly scans for signs that foods are ripe. Colours, scents, congregations of birds, or insects all point to food. For our ancestors, a full belly was preceded by mindfulness. Distraction was a perfect recipe for an empty plate. Many traditional cultures were also mindful of the sustainability of their food supply - Seasonal Mindfulness. Many considered their impact on their children’s children - Generational Mindfulness. I reckon we are deeply drawn to mindfulness, because we understand instinctively that we do better when we are fully present and focused.

Viewed through the eyes of our ancestors, mindful clarity seems like an essential survival skill. In our time-pressured world that same clarity seems critical to Thrive and Adapt when faced with constant change and uncertainty.

And it needn’t take too much time. People have precious little of that already. I don’t know anyone, in any role, who is sitting around with their feet up, wondering what to do with all the spare time they have. The transitions between our many roles get more abrupt with less time to reset between them.

Some transitions you might make today:

Sleeping to awake

Alone to interacting with others in your home

Passive to active

From ‘home self’ to ‘work self’ (clothing, thinking, body language, etc)

From the comfort of home into the ‘world out there’

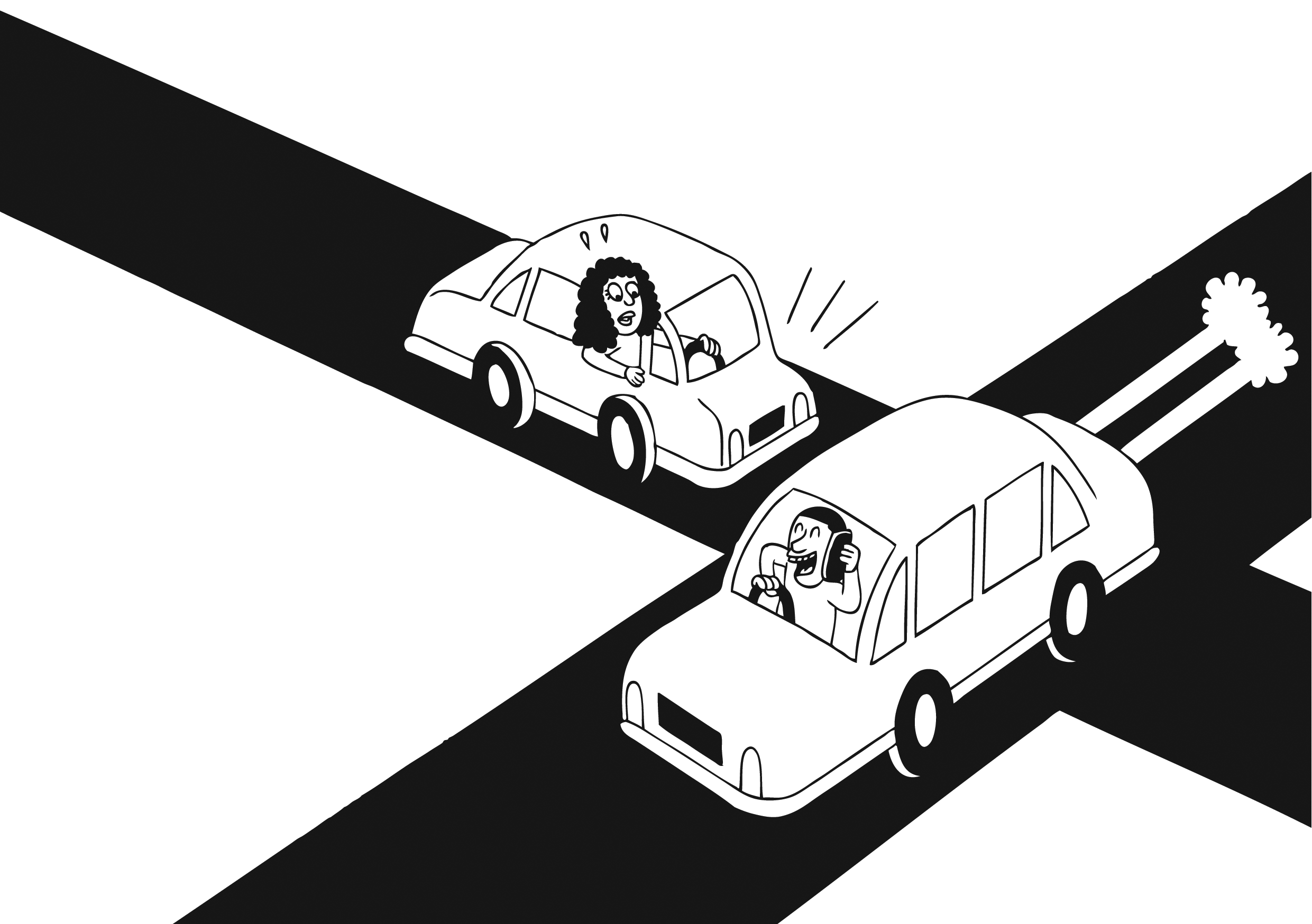

Into and out of transit (cars, trains, bikes, taxis, buses etc.)

Planning to action

Action to review

Into a meeting

Self-directed to directed by a boss/team/task/customer

From following to leading

Into and out of decision-making

Which transitions create the greatest challenges for you?

Which do you slip into without really thinking?

Some transitions are massive, like entering a really important once-in-a-lifetime conversation. Others are small and mundane, sometimes deceiving us with their simplicity and commonality. At each transition pressure can build or dissipate. Each is an opportunity to reset our energy and intention. Or, we can be swept along over the waves and reefs of life, being pushed by circumstances, rather than being in control. If we don’t deal with the tension created at each transition, it builds.

In the short-term, that build-up makes life and work less pleasant and effective than they could be. In the long-term, all those moments potentially add up to one big reckoning, when something big and important gives way, and we are forced to face their accumulation all at once. People face them daily in the form of major health challenges, failed relationships, projects, and businesses. Some pay with their life.

How do you deal with the big and small transitions of your day?

Here's a tool for clarity, presence and focus in the middle of moments of pressure or transition.